From Pioneer to Patient: Discovering Hope in the Teaching of Caring

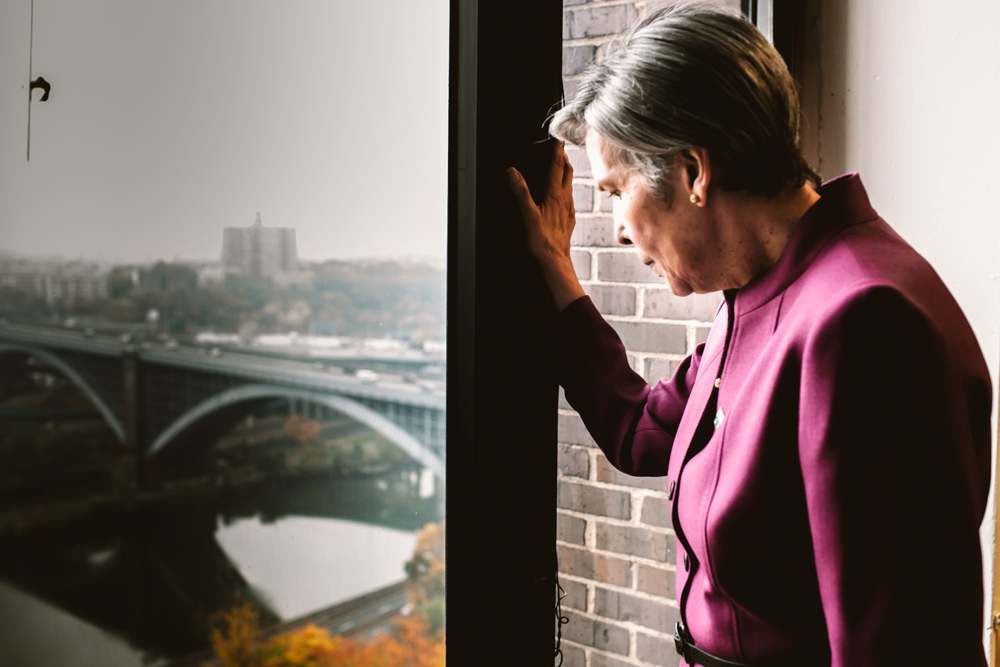

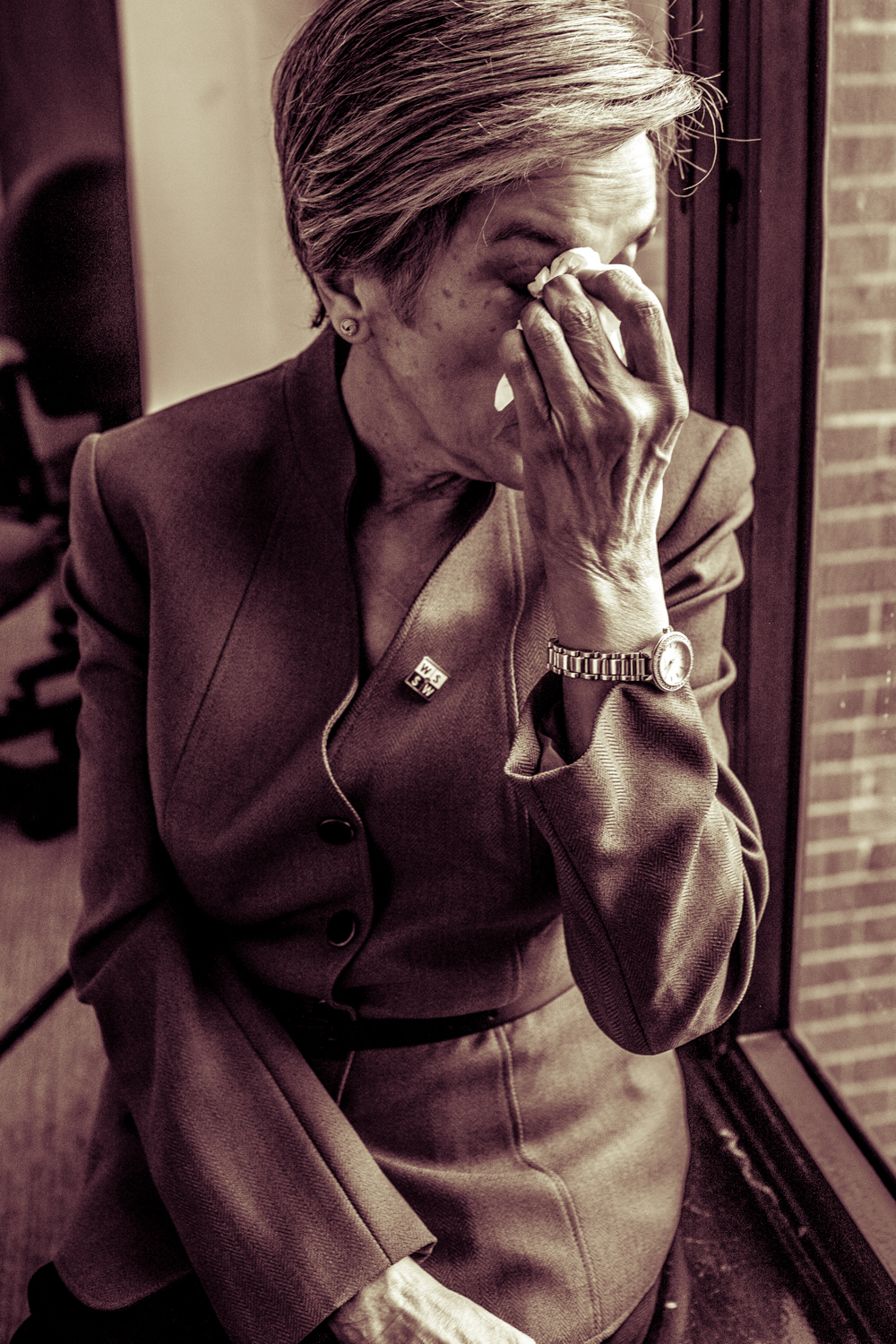

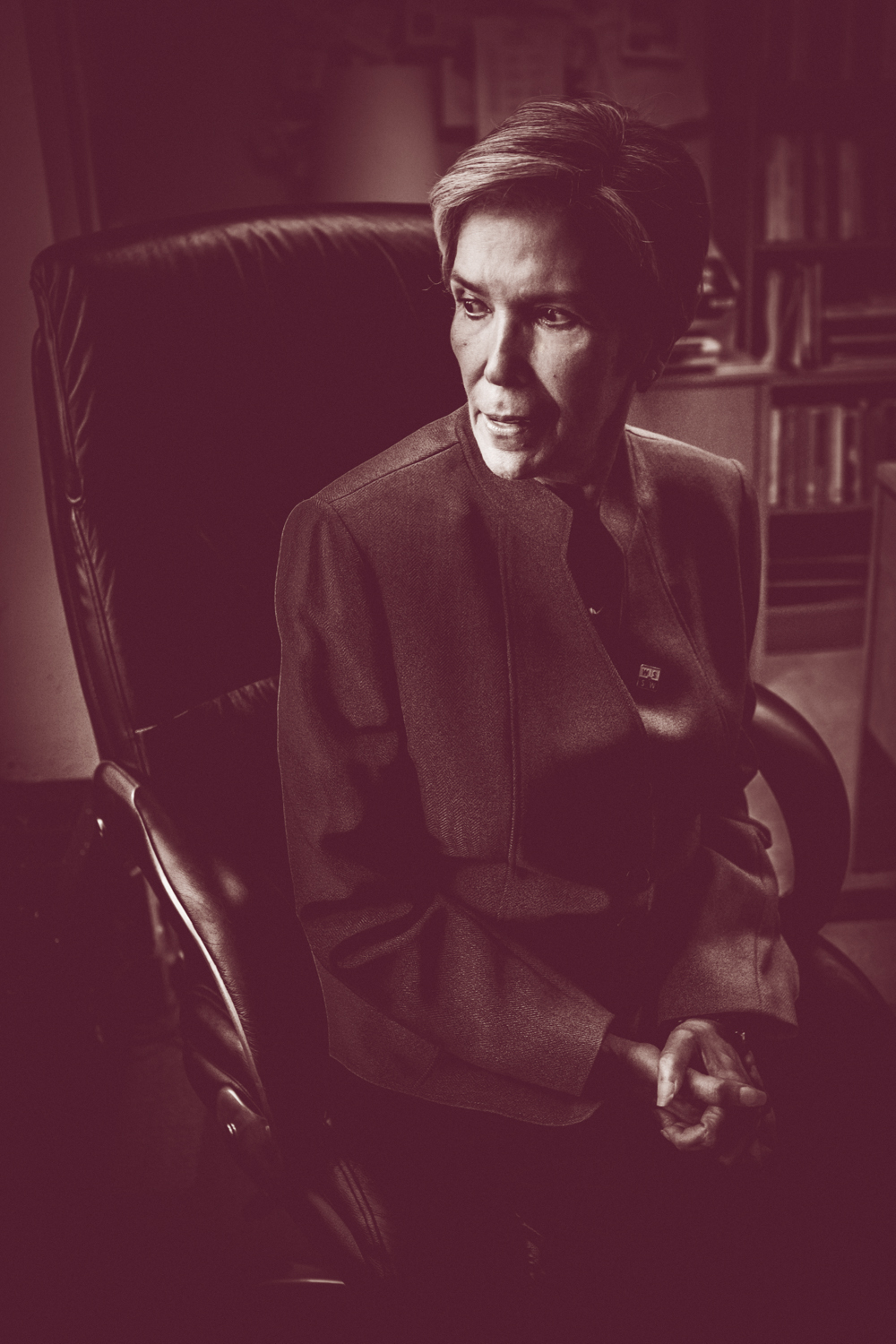

Portraits by Sarah Takako Skinner, Executive Producer of The Hope Is Project

“He told me the diagnosis, and I started crying. I put my sunglasses on, got into a taxi, went home, and opened the door. And started screaming.”

“He told me the diagnosis, and I started crying. I put my sunglasses on, got into a taxi, went home, and opened the door. And started screaming.”

Author’s Update (February 21, 2016)

On February 21st, The Hope Is Project team learned the bitter news that, after a valiant, year long fight against cancer, Dr. Carmen Ortiz Hendricks passed away peacefully and surrounded by her family. We were honored to have known her, and to have been deeply moved by her willingness to share her extraordinary personal story to inspire hope in others. Coupled with her career-long commitment to forging new paths of meaningful service to others, and in particular the Latino community, she leaves behind a world that is immeasurably better for knowing her. Dr. Ortiz Hendricks had much she hoped still to accomplish, and it is a given that her colleagues are committed to seeing those accomplishments realized. Despite this sad news of finality, the story will clearly never end.

This is her story…that Thursday was her worst day.

Dr. Carmen Ortiz Hendricks has had four significant shocks in her life. And the “Ortiz” part of the name? It’s important. The Puerto Rican-born, Catholic-educated Dean of a leading graduate school of social work at a prolific Jewish university is a pioneer and true leader in the field, a professor, a self-taught trailblazer for Hispanic social workers, author, and supportive wife of an entertainer. For almost a year, though, she has primarily been a woman. A woman fighting to stay alive. She has seen her priorities suddenly smashed, transformed into a mortal battle with ovarian cancer.

One day before her diagnosis, she was on top—sitting in her New York City office in a building at the top of Manhattan, both in geography and in elevation, and also soaring at the top of much of the social work world. Fearless, and considering how she will meaningfully shape what would likely be a self-determined final lap of a celebrated career, she was actively making a difference and leading with determination. Having earned her place as a highly-honored and sought-after expert, she has played a principal role in shaping social workers of the future and their resulting immeasurable impact. She would experience the months following that next unexpected day through an emotional and strange kaleidoscope of pain, guilt, fear, tears, love and hope. So long the teacher, she was now a student, learning what it felt like to be in the shoes and hospital gown of so many of those she had helped over the years. And this woman, who many years ago nearly abandoned a career devoted to helping others, would dig deep for courage to reach beyond her fight—in spite of, and as a result of, her challenging experiences—so she could again stand at the front lines of launching careers largely designed to fortify and inspire hope in others. And to find her own path to hope.

Despite the intersection with her new interest of social work, she originally had another more artistic goal in her mind entirely. “I was either in church or in ballet,” she recalls. “I was really heading for ballet and my mother said ‘Over my dead body’, because I wouldn’t be going to college. I was going to go to New York and study ballet, and when I chose social work—everything changed.”

The date of her first professional job was the date of her college prom. “I had broken up with my boyfriend, and wasn’t going to the prom, so I started my $5,800 a year job as a case aid that day. I was very happy.” Spanish-speaking Ortiz Hendricks’ language skills were immediately an asset. “I am sure I was hired partly because I spoke Spanish, and I really started to love social work and what I could do until they put me in charge of the abortion clinic.” It was 1969, abortion was newly legal in New York, and Meadowview Hospital had an abortion clinic. Ortiz Hendricks says that the mother of a priest was a clerk in the clinic, that approximately half the nurses were Catholics, and the clinic was set up to fail. Little did she know that she was about to steer into an important trajectory. “I was young, naïve. It was the law. And I thought ‘What’s wrong with the law?’”.

It was her first real, focused look at discrimination against women. “They thought no one would show up. The first morning, ninety-six women showed up, of every age. Ninety-six. I had to deal with all of this, and it was en eye opener. I became the most dedicated person. I want to help these people. Not just women. The system is set up for them to fail and I want to help them. That sealed it for me.”

Immediately, Ortiz Hendricks wanted to attend social work college. She was young and relied on many mentors, most of whom were Jewish. She reflects, “I asked a mentor why there were so many Jews in social work. She explained about the Torah and that it is built into the religion that giving is a special thing, and why it’s so common for Jews to give to places like hospitals.” Ortiz Hendricks recalls that a majority of her teachers over the years were also Jewish, crediting this, in part, as to why she has spent a good portion of her career at a university under Jewish auspices.

She points to a cup in her office holding several small flags, symbolizing her origin, path and growth. “This is partly why I have an Israeli flag. I have a Puerto Rican flag, the U.S. flag. And the Irish flag because I had sixteen years of Amityville Dominican nuns, most of whom had Irish brogues. So the Israeli flag because of all the Jewish teachers and supervisors, mentors who have had a part in forming of who I am. It’s important for me to remember how I grew up as a social worker.”

“The next thing that happened was I became an expert on the Latino culture.” She was regularly utilized because of her cultural origins and Spanish-speaking, without regard to any actual knowledge base. “I kept saying to people ‘I’m not an expert’, that I’m not even an expert on the Puerto Rican culture because no one ever taught me the Puerto Rican culture.” The budding social worker resisted this pattern and felt disgusted by the ways in which she felt she was being used. She even considered a career-change into computer technology, as it meant she would not have to interact with people. They would not even have to know she spoke Spanish.

“I was being used, and knew it,” she says. She began reflecting upon what was then a lack of attention to the Latino culture within the field of social work. When writing a dissertation on what is feels like to be a minority in a profession, when that same profession was attracting and needed African Americans and Latinos to properly service those communities, Ortiz Hendricks realized that, while this was the future of social work and the country, there was a tremendous disconnect. She even noted that when a Latino student was in the School, culture and country were not discussed. In fact, when Ortiz Hendricks was a Spanish Literature major, she was not even ever assigned to read a Puerto Rican poet. Nonetheless, she claims the biggest ultimate asset to her career was her Spanish language skills at a time when there were few Spanish-speaking social workers. It enlightened her to a need for expertise. “Then I began throwing myself into Spanish culture, reading everything, taught myself to be a culturally competent expert. Although my clients taught me a lot of things, no one else taught me. I made myself an expert.”

Despite an initial disinterest in teaching, sharing what she had learned with others became a passion. Her contributions to developing paths for social work in the Latino community and teaching others to do it resulted in a big surprise in 2009, when she was recognized by the National Association of Social Workers as a Social Work Pioneer. Although amongst other posts and accolades she earned her stripes serving as the president of the New York City Chapter of National Association of Social Workers, was known for work in culturally competent social work education and practice, was a member of NASW’s National Committee on Racial and Ethnic Diversity, helped develop the Standards for Cultural Competence in the Social Work Practice, and is a founding member of the Latino Social Work Task Force, Ortiz Hendricks remains steadfastly modest. “It was a shock. I was only doing my job.”

Despite an initial disinterest in teaching, sharing what she had learned with others became a passion. Her contributions to developing paths for social work in the Latino community and teaching others to do it resulted in a big surprise in 2009, when she was recognized by the National Association of Social Workers as a Social Work Pioneer. Although amongst other posts and accolades she earned her stripes serving as the president of the New York City Chapter of National Association of Social Workers, was known for work in culturally competent social work education and practice, was a member of NASW’s National Committee on Racial and Ethnic Diversity, helped develop the Standards for Cultural Competence in the Social Work Practice, and is a founding member of the Latino Social Work Task Force, Ortiz Hendricks remains steadfastly modest. “It was a shock. I was only doing my job.”

It was a job she had largely taught herself. When she was a professor at Hunter College years earlier, and writing a paper on social work practice, it dawned on her that her own social work practice was teaching. It was an important moment, as she turned the paper around, writing instead about learning her practice through teaching. “No one taught me how to teach or gave me pointers. They just threw a syllabus at me and said to go teach.”

Shortly after Ortiz Hendricks came to work at Yeshiva University’s highly respected Wurzweiler School of Social Work in 2005, a course was offered. It was on teaching. Dr. Sheldon Gelman, another prolific social pioneer and Dean of the graduate school at that time, approached her. “He said ‘You’re gonna kill me. I volunteered you to teach this course.’ But I was ecstatic, and couldn’t wait to teach it. If I were (physically) stronger I would teach that course now.” It was real. She had officially fallen in love with teaching.

When Gelman retired, Ortiz Hendricks said to her husband Jimmy that much of what she heard the president of Yeshiva University say usually related to perspectives of Jewish culture. She was convinced she therefore had little chance of becoming Dean. However, the University’s provost at the time liked her, and she knew being a woman in the environment of this University could be advantageous. On one occasion at a board member’s home, he blurted a response to the suggestion that Ortiz Hendricks could be considered for Dean, that there was already a plan to appoint her. Had it it just happened? “I was shocked as everybody. Everyone applauded and screamed. That was in April 2012 and the president appointed me in July. Sixteen years of Catholic schooling, and religion, helped me. And Jewish and Hispanic cultures have always been friendly, helping one another. Feeding each other, caring for people.”

While having already served in several substantial roles within both the social work and educational fields, Ortiz Hendricks warmly embraced the honor of becoming the first Latina female Dean of Social Work in New York City, a monumental professional accomplishment. And despite her considerable association with the Latino community, assertion of her identity is still a common occurrence. “They think I am in the majority, that I am white. That’s why I keep ‘Ortiz’ in my name. That’s important to maintain my identity. Many of my clients couldn’t even say ‘Hendricks’. I liked having my identity verified by the name, even though you might still have to explain. I had enough explaining of what a social worker was, and didn’t want to explain what a Latina was.” Becoming Dean meant something else, as well. “I wanted to do something for the Hispanic community and ended up doing bigger things than I even wanted to.”

On a Thursday in January of 2015, Ortiz Hendricks had a routine exam. After all, it was only the gynecologist. Afterwards, she was told to see another doctor for a follow-up appointment, and ironically it would be the presence of another social worker that would signal alarm. There was also something about the location that raised concern. “What is this about a cancer center?” she says. “Don’t let that freak you out. Cancer Center? My doctor should have told me. I went there for a physical exam. He brought me into the room and there was a young social worker, a young little thing, maybe twenty-two years old, and I said ‘Uh oh’.”

She was about to receive the third, and biggest, shock of all in her life. The doctor delivered the chilling and life-altering diagnosis. Cancer.

Cancer.

Ortiz Hendricks, a generally sensitive person, is clearly emotional as she recalls these moments. “I started crying.” Because she had not been warned about the significance of this moment in her life, she had not been accompanied by her husband Jimmy (who has been present for every appointment since). She was, and felt, numb and alone.

Sunglasses, taxi, home, door, scream, cry. “I opened the door and started screaming. And crying, and he starts crying. We spent Friday, Saturday, Sunday not raising the blinds, sitting in the dark wondering what were going to do, what’s going to happen. It was the most difficult time for us. But we got through it. We got through it.” On Sunday evening, Ortiz Hendricks’ sister-in-law called, asking for news and why she hadn’t called. “I told her, and eventually I got to the point where I could tell people without crying. It’s awful.” She says she had never seen her husband cry like that. “We came out of it. We went to out to dinner Sunday night. We said we have to take each day as it comes and see what happens.”

The first person Ortiz Hendricks thought of once the initial shock had ebbed was her former colleague, Dr. Adrienne Asch, a Wurzweiler professor who had succumbed a few months earlier to ovarian cancer approximately a year after diagnosis. Ortiz Hendricks’ doctor encouraged her, saying the nature of her cancer was different and her prognosis should be brighter. Then, less than two weeks after diagnosis, a CAT Scan, a planned laparoscopic surgery, and then the new patient is unbelievably hit with yet another major shock.

“Big hullabaloo. My sugar was unbelievable. I didn’t know it. My blood pressure was also bad. The nurse said to me ‘Honey you’re getting another diagnosis.’ I said ‘What?! Diabetic? Oh, please don’t tell me that!’” Fortunately, in the last ten months, Ortiz Hendricks’ blood sugar been managed to a more acceptable level and she is hopeful it will remain there. “I don’t want diabetes. My mother was diabetic. These were the worst moments of my life. To hear that diagnosis, and to think I’m dying. That’s what we thought—that I’m going to die.”

On top of having to navigate her sugar levels and blood pressure, the impact of chemotherapy, which started only a week after surgery, was gradual but powerful. The fight has now taken nearly an entire year of her life. She worked for another three months until, at a special event, she required the assistance of three people so she could rise from a chair. That was unacceptable to her. It was undignified, embarrassing, and she feared it made others uncomfortable. She was determined not to return until she could be independent and free from crippling weakness.

The road has been excruciating and often without sufficient guidance. “I wish the nurses would explain better,” she says. “I hear them in different rooms. They explained it better to different patients, no one explained to me that what I’m going to suffer from is the chemo. The chemo’s the bad part. I wish someone had told me, but it wouldn’t have helped anyway.” The tingling and the sharp pains were among the largest challenges in the fight to recover, she says. “Painful, painful, painful. You can’t imagine how much pain I’ve been through. It’s been awful. I’d lay there saying ‘Shoot me, kill me, I can’t take it anymore.’ He’d say ‘You have to be strong.’ Surprisingly, I really never got nauseous. I could eat a few bites, but then throw up.”

Her husband was extremely concerned about her resulting dramatic weight loss. Now that Ortiz Hendricks is eating, he works tirelessly to find meals that excite her. Interestingly, she most craves greens and tomatoes. “He’s a good cook. I could tell you all the things he made for me that I couldn’t eat. The man tried so hard. The only time he gets upset is when I don’t eat. He’s happy to see me walking.”

There was indeed a darker period. For months, Ortiz Hendricks was out of touch with family, friends and colleagues, receding into a life of absence and seclusion. She did not come to work or answer most calls, and could not manage the mounting emails. In addition to tremendous discomfort, depression and pain, she shut out the world. “I was feeling guilty that I wasn’t taking care of business. I felt like I abandoned my team at work. I was just laying on the sofa, moaning and groaning. It was not nice, and I was in pain, but also feeling guilty.” In August, she realized she was no longer constantly moaning and groaning, and was able to sleep through the night. Soon after, she began reestablishing contact and making her way through mountains of emails. And coming in to work again.

It was an important moment for her, and equally important for her colleagues to see their leader return. First a walker and a scooter, and now a cane. She has been maintaining a schedule of at least three days in the office weekly, doing what she can from home on other days, but wanting more, despite often quickly reaching exhaustion. At this point, merely a few hundred emails remain unread, but the guilt remains. “I hate seeing that number. It reminds me of my neglect. It’s a reward that my colleagues don’t feel I neglected them, but I do. I felt extremely bad that I couldn’t do more. Jimmy said ‘When you get better, you will do more.’”

Despite resuming her continuing influential leadership roles, even the small accomplishments in her personal life, such as taking out the trash, give Ortiz Hendricks great joy. “I did two loads of laundry the other day, and was so proud of myself. The neighbor Larry makes me cry, seeing me doing laundry, and saying ‘This is a sight I haven’t seen in a long time,’ and it makes me happy.”

One thing she had not anticipated was how much she was loved and cared for, often by people who surprised her by their unexpected affection. “How many presents, flowers. So heartening, I can feel good about myself. I know my funeral would be crowded. But I worry about my husband Jimmy. He’s wearing himself out.” Recently, a walk up a ramp to a CAT scan appointment with a cane brought a sense of pride and accomplishment. “I see an old lady in the mirror, I see my mother. I’m scrawny now. But these improvements give me hope. I am hopeful now that I can get better.”

On the subject of hope, at the time of this interview Ortiz Hendricks is awaiting a call with the CAT scan results. She has been waiting for several days and is anxious “It’s been awful. Worse than I could imagine. When it got very bad, all I could do was stay at home and sleep and moan. But I have no pains in my stomach. I don’t feel cancer in there, I don’t have cramps. I don’t have anything I can point to and say ‘Oh, there’s the cancer growing.’ They are going take out my tubes, they are going take out my womb, going to take out everything. So long as they take out the cancer, that’s fine with me!”

As with many cancer patients, Ortiz Hendricks is concerned about the possibility of metastasization to other organs such as the bladder, liver or kidneys. “That’s what I’m afraid of.’ Her voice trembles with emotion. “I can’t tell you how many times I’ve thought of Adrienne.”

Wurzweiler is important to Ortiz Hendricks, having given her the opportunity to be a bona fide leader in the profession, and not just in reputation. She muses about the possibility of a remarkably ironic closing of the circle of her life, warmly returning to something she had once resisted. “It gave me the first chance to do some of things I wanted to do. I still want to create a Hispanic track in the School.” She talks of the School as a truly special place, partly due to it’s small size, hands-on experience and intimacy. A place where people care.

And for Ortiz Hendricks, hope is all about one word. Caring.

She hopes she will be healthy enough to see and reconnect with her beloved colleagues at the National Association of Deans and Directors a few more times, and not to feel cut off from all of them. Then she again becomes emotional when discussing her great nieces and nephews. “I want to see them grow. I don’t want to miss them grow up. That makes me sad that I won’t be able to be there for them. They are the future, they’re my hope. I am waiting for someone else to get pregnant in this family again. I want more.”

And then there is Jimmy. Her husband, a professional actor, is likely best known as the title character in the 1980’s USA Network TV series “Commander USA’s Groovie Movie,” amongst other film, television and theater credits. For Ortiz Hendricks, his best work might be center stage as a focus of her sense of hope. “My hope is to spend as much time as possible with Jimmy. He’s my best friend and supports me in everything I do. I’ve learned from him, more than anybody else, patience and to do what you can, don’t feel guilty about not doing something.”

She mentions his nature as a “free spirit” and admires that he’s followed a path of his choice. “He says thank you every once one in a while, because I helped him to do what he wanted with his life. I was the breadwinner, he was the actor.” She notes that he can turn any line into a laugh. “That’s what he’s done for me, he’s kept me laughing these many months. If laughing is what keeps you alive, I think I have a wonderful partner in him. I just want to spend as much time as I can with him. That’s my hope.”

Ortiz Hendricks takes a moment, considering the bigger picture. “I have never said ‘Why me?’. It changes perspective, you think of health, illness, will I eat today, I gotta take all these pills. It changes perspective.” When asked if that new perspective includes the way she approaches social work or its education, she admits “It made me better. More empathetic than I thought I could be. I am basically an empathetic person, I feel for people, I cry at the ‘Star Spangled Banner’. Yet, I don’t think I’ve let this affect me that much. I am a more dedicated administrator, bound and determined to deal with challenges at hand.” Indeed, there was a time this social work educator had no interest in even being an educator. And now, “if I could teach, I would probably be the same kind of teacher I’ve always been, very caring and involved in student’s learning.”

Participating in The Hope Is Project, looking for images of hope and photographing them with purpose, has provided Ortiz Hendricks pause to really think about what hopes she has that propel her forward in the midst of considerable challenges. Reconnecting with her colleagues. Watching children grow. Time with her beloved Jimmy. While in the hospital for a CAT scan, even the “machine monster” standing in the hallway made her think of hope. It looms with ominous appearance, and then one gets into it. It talks to its occupant, directing one to hold one’s breath, calmly coaching when breathing is allowed. “The first time was a long time, I thought it would never let me breathe. This machine tells you what’s inside your body. There is real hope in the fact that the message can be good news.”

And then, there is one more thing. One more place she looks. It is as much a retrospective reflection of her life as it is a view of the future. “It’s the students, though. It’s them. The future social workers. They are my hope.”

To see more photos taken by Dr. Ortiz Hendricks, and more of her portraits captured by Takako, visit http://hopeisproject.com/pioneer

FROM THE EDITOR

At Conscious, we feature powerful stories about global initiatives, innovation, community development, social impact and more. You can read more stories like this and connect with a growing community of global leaders when you join.