Future Of Media And The Integrity Of Journalism [Issue 03 Exclusive]

With technology creating new mediums for a growing media landscape, the integrity of journalism must remain at the forefront of our thinking.

The role of media hasn’t changed much since America’s first tabloids were published more than 300 years ago. Stories ranged from military initiatives, partisan opinions, and more mundane matters like the weather. What has changed is the way in which media engages us and makes us feel about ourselves, those around us, and the world we live in today.

Today’s media landscape is often viewed as a minefield, filled with negative imagery, toxic messaging, and advertising disguised as editorial. Add in the multiple digital platforms at our disposal, and you have an infinite number of potentially nefarious communication channels to navigate. Yet, if we tread carefully, we can still find good content that informs us and provides insights that ignite discussion, broaden our views, and possibly create greater change.

Medill’s Integrated Marketing Communications Lecturer, Judy Ungar Franks, talks with both her undergraduate and graduate students about today’s media landscape as a system transforming from a state of chaos into a state of clarity. She explains that chaos, as defined in nature, is not negative but evolutionary and critical to a new re-ordered state: “If the media system stays at rest for too long, it becomes unhealthy and sick like any organism. This notion of moving from a media system of rest to a media system of chaos is necessary and helpful.”

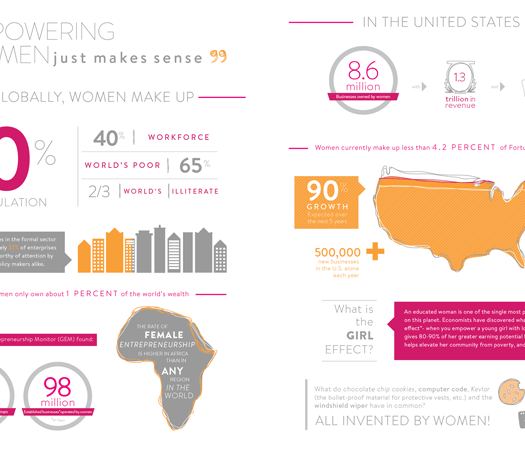

The democratization of the media happened when consumers were offered a broader choice of what to read, where to read it, and how to engage with its content. Many say that this shift happened with the creation and expansion of digital media, but Franks disagrees by saying, “It wasn’t digital media that threw the system in chaos, but the proliferation of choices from different media sectors like print, television and radio. As soon as we had individual choices, it started to enable and empower audiences to select content that best served their needs.” Franks refers to this as “content economics,” where the content attracts the audience much more than the platform.

According to a 2014 American Press Institute Report, Americans choose to get their news from a variety of sources and devices. This research, conducted by the Media Insight Project (an initiative of the American Press Institute and the Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research) not only debunks the notion that media consumption is divided along generational and political lines, but also that the nature of the news itself largely determines where people go to learn about the subject and the path that they take to obtain it. Topics such as politics, crime, sports, and culture dictate how the news is received regardless of the demographic. The report also suggests that Americans are becoming more comfortable using technology and sourcing stories directly from the mediums and devices that prove most useful to them.

So, if people are consuming the news on multiple platforms using multiple channels and sources, then who’s vetting the contributors, monitoring their content, and ensuring that the standards and ethics of good journalism are applied?

Some prescribe to the notion that a new set of standards are required to accommodate digital media’s diverse content sites. Some say that it’s becoming increasingly difficult to impose journalism’s original code of ethics (accuracy, research, transparency, diverse sourcing, and unbiased reporting) to the immediacy of digital storytelling that relies on same-day deadlines and real-time reporting, which often utilizes citizen “journalists.”

Many journalism schools are responding and shifting their curriculum to contain coursework that includes digital storytelling and multimedia platforms. By the nature of the profession, ethics are more critical than ever.

Edward Wasserman, Dean of the Graduate School of Journalism at the University of California Berkeley, believes that his curriculum is meeting the needs of today’s journalists. “The first challenge with our students is to make sure that they can use the most appropriate and elegant technologies that are available for the story they want to tell. The harder part is to teach them to negotiate the informational landscape. It’s so rich with so many sources for reporters now. We’re making sure they are more skeptical interpreters of information now,” Wasserman says. “We try to differentiate what journalists do and what other people do, which is traffic topical information.”

It’s an exciting time for consumers (and journalists), as consumers are driving stories digitally by becoming the gatekeepers of information. The hope is that within the stories that we share, there are stories that provide positive reinforcement and propel change. Wasserman says, “I see a bright future for journalism. There’s a hunger for fact-based narrative and topical commentary, and the number of distribution channels out there can be more effective and more powerful than ever.”

Tips for Finding Good Stories

By Edward Wasserman

-

Browse widely. There are some very interesting, fresh, and imaginative news-based sites. Some are fiercely experimental and are trying to devise different forms of storytelling.

-

Spend time looking around the Internet and follow up on hyperlinks of sites that you already trust, which will expand your own news network and imagination.

-

Look at overseas sites. There’s a tremendous amount of experimentation happening from people that are sending out information from highly controlled environments.

-

The tools of making information go public have been universalized, and often stories are being shared before they’ve been edited, so it is up to the consumer to be cognizant and discerning.