Women’s Rights Are Human Rights [Issue 03 Exclusive]

As our society progresses into the future, it is unfortunate that gender inequality and lack of women’s rights remain prevalent around the world.

Meet Anna Squires Levine: a beautiful, soft-spoken, petite, and young woman, who at just 28 is the President of Born Free Africa, an initiative to end mother-to-child transmission of HIV by the end of 2015.

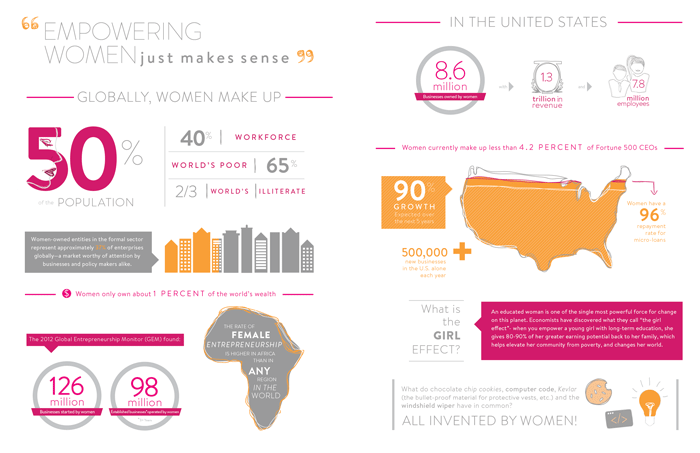

Anna splits her time between New York City (where she calls home as a newlywed with her husband) and traversing the Atlantic a few times a month. During her travel, she is advising various African government and business leaders on talent acquisition to drive change towards the elimination of HIV/AIDS transmissions throughout rural Africa. Imagine the scene: Kenya, dusty, hot, and hectic. There, Anna is speaking with various suited astute male business leaders: “I am often the only woman, the youngest, and the only white person in the room. At first, when someone would mistake me for President Levine’s assistant, it would make me fume.” This case of mistaken identity may not seem too surprising given the context in which she works. However, when we consider women in the United States make-up less than 4 percent of all Fortune 500 CEOs and women account for only 21 percent of Parliamentary seats worldwide, the scene becomes much less unusual. Yet, Anna is breaking all the societal norms and statistics about what it means to be a woman in leadership and government internationally, and she’s not the only one.

In March 2014 when the Ebola outbreak was surging, many of the affected countries descended into a total panic, lacking the proper public health infrastructure to support patient care and community engagement. Much of the spread of Ebola was due in part to the communication breakdown between systems that simply couldn’t withstand a catastrophe of this magnitude. In a matter of twelve months since the outbreak began, over 27,000 people died. Camilla Hermann, 25, had been working in Ghana since she was a college sophomore within the Buduburam refugee camp, where she founded a non-profit that sought to provide for basic needs of vulnerable women and supported the Liberian Embassy on repatriation efforts for over three thousand unregistered refugees. As the Ebola outbreak worsened and international agencies delayed, Camilla says she wondered why there wasn’t a greater focus on mobile technologies: “From my time in Ghana and Liberia, I knew that telecommunications formed the backbone of infrastructure for these countries; it is how people survive. Roads and power lines are critical, but they don’t reach as far as mobile does. If you’re trying to reach target populations with life-saving information and care, why not leverage this tool?” From there, Camilla, just two years post-college graduation, decided to build, pilot, and work to implement the Assisted Contact Tracing (ACT), a technical platform that uses dialect-specific voice recognition to trace contacts, outbreaks and where viruses (such as Ebola) will spread.

When you meet Anna or Camilla in person, their actual careers would likely be the farthest thing to cross your mind. You could easily mistake them for having just finished college, yet both have chosen unlikely paths in an unforgiving land. When asked why her, why now, why Camilla, she said, “Why the hell not me? This was something concrete I could contribute. So, I did.” From an early age, Camilla and Anna have held a no holds barred approach to confronting and kicking in the face the “social graces” expected of them as young women.

While slightly less unusual amongst the pioneers of so many influential women leaders young and old often seen gracing the covers magazines or in the media, both still remained the exception to the rules and not the norm when compared to the world at large. Women make up 40 percent of the world’s workforce, yet they only own 1 percent of the world’s wealth. Even more surprising, more than one hundred countries have laws on the books that restrict women’s participation in the economy.

Sprinkled throughout the globe and largely throughout Africa where women work, the gender gap reigns loud and clear-women and girls are struggling to stake claim to equal pay, equal education, and equal rights. Let’s rephrase: women and girls are struggling to claim basic human rights, which should be afforded to all of us.

An hour outside of Zambia’s capital, Lusaka, we find a different scene. In a small four-room mud dwelling, home to sixteen people (five adults and eleven children), Dr. Chipepo Chibesakunda, 33, Zambian by birth and Cuban by education, and Mrs. Nandala, Deputy Head at the local primary school (Shalubala Upper Basic), are both visiting with a 16-year-old girl, who we shall refer to as Mary. Just a teenager, Mary’s already been married and divorced from an abusive older husband. Unfortunately, this is not the exception to the rule for sub-Saharan Africa, but again, this is the norm, as 80 percent of girls are married before the age of 18. Mrs. Nandala remembers Mary as “a bright and strong reader,” when she attended her school up to second grade before dropping out at 12 to be married. “You had so much potential,” Mrs. Nandala urged, “Come back to school; we will work something out.” The young girl shyly shakes her head, “No.” Dr. Chibesakunda leaned over looking intently into Mary’s eyes urging her in their native Nyanja language. The young girl looked nervously between the two fixed gazes of the women, and then again lowers her head. Dr. Chibesakunda translated, “I am telling her that I am a woman too. I said, ‘Look, if I can do it, you can too.’”

Sadly, this isn’t just a Zambian story. It is a reflection of more than 39,000 girls who are forced into early marriage every day and are not in school. Nearly seventeen percent of the world’s adult population is still not literate; two thirds of them are women, which is making gender equality even harder to achieve.

Despite the gnawing sense that women empowerment has not reached these local villages and other areas like them throughout the Global South, women like Dr. Chibesakunda and Mrs. Nandala indicate that perhaps attitudes are beginning to shift away from the rural “tribal” cultural and subjugated “honor code” as seen throughout the Middle East and South Asia. “If you don’t have a husband, then you’re not making it. Now, we are showing them that if you have a job, you can make it without a husband. It’s thinking beyond the village mentality,” says Dr. Chibesakunda. If girls like Mary weren’t limited by the cultural norms keeping them from reaching their full potential and (were instead) encouraged and afforded the same opportunities to education, vocational training as their male counterparts, then it is estimated their increased participation in the global economy could alone provide 140 million people with food.

Nick Kristof says in his New York Times blog, “On the Ground” – “It’s a reminder that the struggle to achieve gender equality is not a battle between the sexes, but something far more subtle. It’s often about misogyny and paternalism, but those are values that are absorbed and transmitted almost as much by women as by men.” Komal Minhas, documentary producer of Dream, Girl adds, “The world is connected at levels never experienced before. As a result, we have greater awareness of economic failure, war and egregious human rights violations happening all over the world. The way the world has been operating has led to crisis upon crisis. We need to fundamentally shift how we do things, and this starts with empowering women and girls to take control of their lives and the future of this planet.”

Empowering women just makes sense. It increases our global GDP and yields the highest return on investments for countries. It’s a proven fact that an educated woman is one of the single most powerful forces for change on this planet. When you empower a young girl with long-term education, she gives 80 to 90 percent of her greater earning potential back into her family, which elevates her family from poverty and changes her world.

In some countries, eliminating barriers to employment for girls and women could raise labor productivity by 25 percent. “When girls get educated, when women enter the formal labor force, when female talent can be realized, then all society benefits, men along with women. That’s because, put simply, the most effective way to fight global poverty, to reduce civil conflict, even to reduce long-term carbon emissions, is typically to invest in girls’ education and bring women into the formal labor force. Investment in women is an idea that is gaining ground lately because it is a proven strategy that works,” added Nick Kristof.

A few days later, Dr. Chibesakunda visited Shalubala Upper Basic School to cover Mary’s school fees, so that at 16, Mary could become a student again. When we walked outside the magistrate’s office to greet Mary, we learned she had skipped off to purchase her new notebook. A teacher approached us, brimming with pride, “How is Mary doing?” Dr. Chibesakunda asked. “She wants to be a doctor one day,” he replied.

As Marian Wright Edelman, founder and president of the Children’s Defense Fund says in the documentary, Miss Representation: “You can’t be what you can’t see.” If we empowered women, would the world change that much? Yes, the answer to that question is a hundred times: “Yes!” Women like Anna, Camilla, and Dr. Chibesakunda are showing us that human rights are women’s rights, and women’s rights are human rights. It’s high time we joined the fight for one half of humanity to start lifting the other half of humanity up. It just makes financial sense, as the future of our world depends on it.